I can do a party trick: Give me any controversial topic and a laptop with wifi. After ten minutes, I will come back with two completely conflicting perspectives backed up with studies that I can make appear absolutely credible to you.

An example: Should I breastfeed my baby?

Position one: I should breastfeed my baby. Studies show that it has positive effects on babies’ health outcomes. For example, a study by Murphy et al. from 2023 compares 2212 exclusively breastfed babies with 3987 babies who were not all born and cared for in Ireland. The authors find that exclusively breastfeeding for 90+ days is associated with protection against childhood morbidity. For instance, they are less likely to develop respiratory diseases, including asthma and chest infections, and spend less time in the hospital. Convinced?

Position two: It’s totally ok to bottlefeed my baby. A study by Colen and Ramey in 2014 found that breastfeeding does not significantly affect the long-term health of children in 10 out of 11 commonly used indicators for child wellbeing (such as BMI/obesity, asthma, hyperactivity, attachment, compliance, academic achievement, and competence). This study is based on 25 years of panel data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth in the US. By studying sibling pairs where one sibling was breastfed and the other bottle-fed, the study concludes that “many reported beneficial long-term effects typically attributed to breastfeeding may primarily be due to selection pressures into infant feeding practices along key demographic characteristics such as race and socioeconomic status.” Also convincing.

Which study will you believe? The short answer: Whichever study more closely aligns with your preconceived notions and those of those around you.

(Because this is an essay about bringing the personal into how we consume research and make decisions: Ben was bottle-fed. But also: Please keep reading. I’m largely finished making you read entire paragraphs synthesizing medical research.)

Here are a few similar, patently researchable questions I grappled with while pregnant: Do I continue taking a mild anti-depressant? Do I completely cut out alcohol? Which foods do I restrict, if any? While I’m happy to share my answers (yes, most tuna and unpasteurized cheese), the answers aren’t really the point. But sometimes, late at night in bed, listening for my baby’s quiet breathing, I torture myself over new questions and still struggle with how I can come to a satisfactory answer: Should I give Ben food that contains salt? What about refined sugar? How safe is co-sleeping? How do I raise a trilingual child? Etc. (and etc., etc.).

When we started trying for a baby, my husband and I felt very smug about our ability to make well-founded decisions on pregnancy, birth, and babyhood by doing our own research. After all, I have a PhD in political science and work as an applied researcher in gender diversity and DE&I, all of which seem to make me well-equipped to approach this research challenge. My husband studied econometrics at university and is an Excel whiz (one time, Tom asked me what I consider his biggest strength, and I blurted out, “Excel.” I’m sorry, my empathetic, adventurous, kind husband.) Together, we could form a small interdisciplinary, mixed-methods research tandem.

We could be forgiven for believing that we could make informed decisions regarding our family planning journey by looking at the relevant research. You could be forgiven for thinking that your choices are well-informed, too.

Research is “me-search”. Derided by BBC News as "academic narcissism" and "diary-writing for the over-educated," this twee term refers to either autoethnography (a researcher uses their personal experiences to answer academic questions) or, more broadly, to choosing research topics because of some personal motivation. My own personal “me-search” journey found me pregnant and sweaty, nauseous, and/or fatigued on the couch, scrolling r/BabyBumps on Reddit. The degree of certainty displayed by Redditors about key pregnancy decisions is staggering, as is their vitriol for those who disagree with them. Reddit did not change my mind about any pregnancy decisions I had already made, but it sure had me stressed.

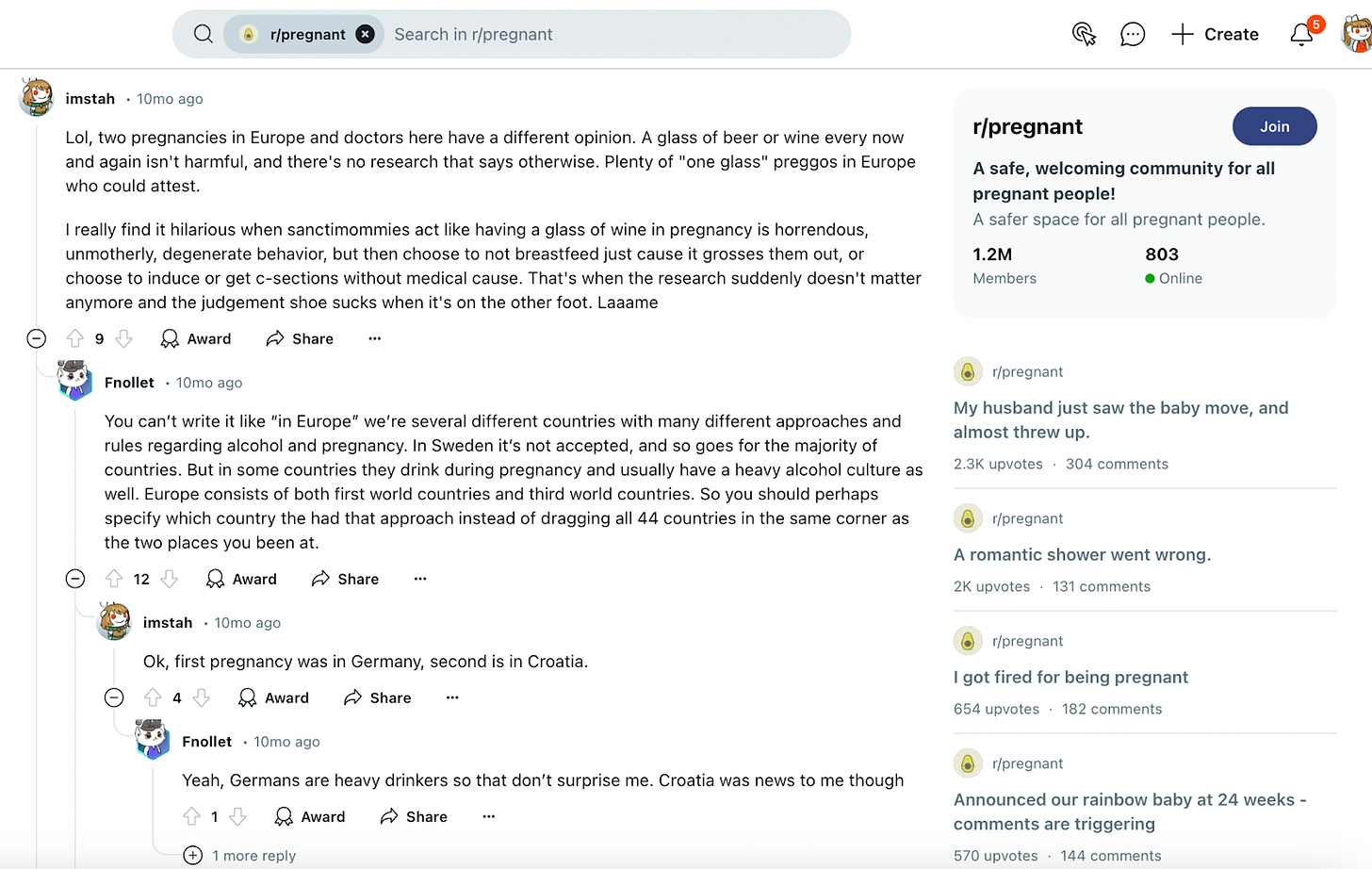

For example, here’s the advice u/oilydischarge18 gave to u/Olt1994 about the continued use of antidepressants in pregnancy: “You can absolutely stay on antidepressants. A depressed mother is much worse for a baby than some of the medications available.” Chimed in user u/RottenPotato1020: “Sweetheart, do not talk to your GP about this, they are not qualified like an OB. Your OB would definitely want you on the meds. Sertraline is very safe in pregnancy and breastfeeding. ❤️” Or, finally, says u/imstah about drinking wine while pregnant: “I really find it hilarious when sanctimommies act like having a glass of wine in pregnancy is horrendous, unmotherly, degenerate behavior, but then choose to not breastfeed just cause it grosses them out, or choose to induce or get c-sections without medical cause. That's when the research suddenly doesn't matter anymore and the judgement shoe sucks when it's on the other foot. Laaame [sic].”

In qualitative research, the researcher often reveals details about their personal situation and identity and reflects on how they might influence their perspective on the subject matter (this is called “positionality”). Consuming research (or others’ interpretation of the research) while pregnant has shown me that my own vulnerability also affects how I consume and disseminate research.

There is nothing dispassionate or objective about consuming pregnancy research while pregnant. There is so much pressure on pregnant women and women who want to be mothers to get it right. Put more eloquently by Meeussen and Van Laar: “Intensive mothering norms prescribe women to be perfect mothers. Recent research has shown that women’s experiences of pressure toward perfect parenting are related to higher levels of guilt and stress. “ Social media makes this worse: The heavily curated, filter-overlaid aesthetic of mommy influencers’ Instagram posts tempt (future) mothers to compare their inside to other people’s outside, which increases envy and anxiety and can ultimately be harmful to new mothers’ mental health, argue Kirkpatrick and Lee.

There are hundreds of decisions to make while pregnant (hormonal, so fucking tired) and caring for a fragile newborn (so fucking tired). U/gracefulendeavors shares on r/pregnant how she feels making decisions about her soon-to-arrive baby: “I know people who have lost their baby while bed-sharing and also while the baby was sleeping in their own bed. I am terrified of when my baby arrives to even let them sleep.” This reads chillingly familiar. Every time Tom and I made a decision about, say, how I could feed myself during pregnancy, I would ask him, for days, a truly broken, tired, cranky, bloated record: “I’m not harming our baby by eating basil, right? It will be ok, right?” (This was after I ate a Caprese salad in front of an acquaintance who promptly asked me, very seriously: “You’re still eating basil?!”)

Nowadays, being a perfect mother includes asking all the right questions, consuming all the right sources, and thus, making all the right decisions. And all of these decisions, ,as the people of Reddit or your friendly neighborhood mommies Facebook group, will surely tell you, are literally life and death. Get it right, you’re still not good enough. Get it wrong, and God help you.

In a turn of irony befitting Alanis Morisette, the research you are supposed to do is, in fact, inaccessible by design, at least in its original form, the published journal article. Most studies published in academic journals are hidden behind high paywalls (the going rate is about 35$ per article, though you can always email the author for a copy – authors of academic journal articles do not earn royalties but profit from their work being widely disseminated). What is more, much research targets a tiny, very specific audience in how it is written (not well), has a high degree of information density, is based on methods that take years of study to comprehend fully, and is full of (multi-syllable-)jargon.

There are so many consumers of second-, third-, and fourth-hand interpretations of the science (say, through journal articles, books, government recommendations, hospital guidelines, OBGYNs, midwives, friends, colleagues, and, yes, r/baby-bumps and your prenatal yoga class’s Whatsapp group). In Switzerland alone, 38’811 women had their first child in 2023. That’s not even counting those who’ve already had a child or want to be pregnant or their partners. And for all of us, the stakes are sky-high: Am I truly doing what’s best for my baby? Am I a good mom? All of us amateur researchers are overwhelmed, stressed, and so scared. So we get defensive - because we simply have to get it right, or so we’re told. And many of those who advise us have incentives to skew advice a certain way. In the wise words of u/PersimmonQueen83: “I think the guidelines given to the public are so hardcore because organizations like the CDC feel like they cannot even open that door a little because people will abuse it.”

So begins a game of telephone, where we repeat the same snippets of research over and over. There is no known safe quantity of alcohol during pregnancy, we yell into the voids of Reddit, Facebook, and our baby care course, because we have to believe that there are some clear and simple rules in this rigged game. “The science,” at the very least, should be a firm foundation on which to build a healthy baby that will grow into a thriving child. But pregnancy research, which most of us can’t understand (I know I couldn’t), turns into rumors.

So how can you get out of the rumor mill? How can you become a better consumer of pregnancy research? Remember: Published papers are not truths etched in stone. Apart from repeating this to myself like a mantra, an actual, immutable truth in a moment of intense uncertainty, I like to ask myself the following questions when consuming research in any form:

What do the author(s) want to know? What is their motivation? And, most importantly: Does this align with the motivation that you brought to reading the study?

How is the outcome of interest measured? Who/what are the subjects, and do their circumstances resemble yours enough to make the study applicable to help you out in your situation?

Are there other, equally likely, explanations for what is observed? (For example, breastfeeding parents are more likely to be well-educated and wealthy than bottle-feeding parents. Could this be an explanation for better health outcomes in breastfed babies?)

Take time to ask yourself, and be honest: Do I find this conclusion compelling because it affirms something I already think (or wish) is true? Or am I discounting their findings because they differ from what I expect? (Also filed under: Confirmation bias)

But reading studies didn’t make me feel armored against the pregnancy science rumor mill (nor did Reddit). In the end, what worked for me? I chose my fighter: I would trust my OBGYN with my life (I mean, I sort of did). She knows me and my circumstances, my body, my medical history; she knows the research; she understands the science. I chose to trust her judgment on all questions, (almost) no further questions asked.

And I tell myself, over and over again: None of us know. We’re all doing fine. And then I open Reddit.

Study Guide:

Economics Professor Emily Oster has built a vast body of work based on her own realization, early in her first pregnancy, that there is very little concrete advice she is getting on what she is and is not allowed to do. Read her book, Expecting Better; consult her website, Parent Data. Or listen to her podcast of the same name, wherever you listen to podcasts. There are aspects that I disagreed with (and Reddit has strong opinions, of course), but I always trust meta-analyses more than any single study, and I found the book especially to provide a well-written, accessible meta-analysis.

If you want to read even more about reading scientific papers, don’t let me stop you. I likeTen simple rules for reading a scientific paper as a primer on consuming published studies by Maureen A. Carey,* Kevin L. Steiner, and William A. Petri, Jr, who are computational biologists, but this doesn’t affect the paper.

Love your article. I have a question about the concept of 'me-search' (as I'm very much guilty of it). What research topic is not chosen for personal motivation? To support, to oppose, to change, to deepen, or, simply, to understand ourselves - all research to some degree is personal and self-motivated, if a researcher can hope to create a sustainable study habit. Or is the point of ‘me-search’ more about confirmation bias? Anyway, keep it up :)

I love this, and all of this resonates. So relieved that my toddler is an unstoppable force of his own with incredibly strong opinions and willpower to follow through (that I lack), so it doesn't matter what I think we should do, he's just going to do what he plans to do anyway.